John and Mary Lou Anderson were once our neighbors with whom we shared occasional meals and guard duty when either of our families went on vacations. We had each other’s house keys and I knew how to water their marigolds the way they liked. They have lived in this same house near Bancroft Tower for almost forty years, but we have long since moved away to another neighborhood off of Flagg Street. As I started to ponder questions about the history of the building of Route 290 and its impact on East Side neighborhoods, I knew John was the one to call to get some answers. Was the rumor true that the powers-that-be at the time wanted to break up those thriving immigrant neighborhoods emerging as a power threatening voting block? No, that was not true, John assured me, but he explained in great detail how the highway impacted each neighborhood. John gives us true wisdom derived from his being a lifelong Worcester resident, a historian with a particular expertise in Worcester history and a shaper of public policy during his twenty- two year career as city councilor (1975 – 1997). He even served as mayor in 1986. In this conversation, he reflects on his public service contribution to the city.

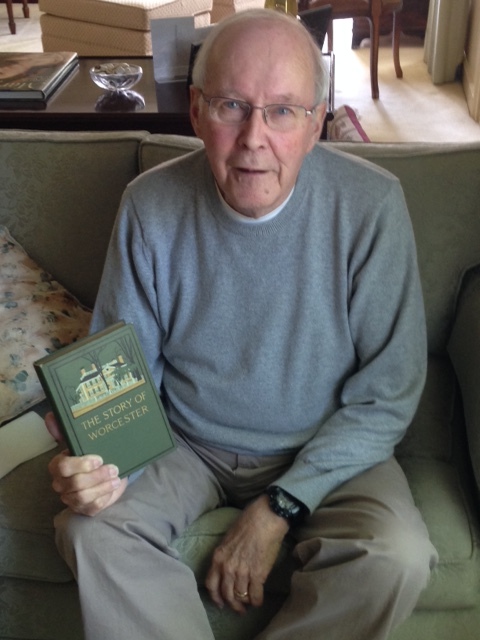

John tells me about a new exhibit being curated at the Worcester Historical Museum called "Worcester in 50 objects." When I asked him what object he would share to symbolize his Worcester connection, he retrieved this book from his basement. "Everyone who lives in Worcester should know our history," he smiled. What object would you choose to tell your own Worcester story?

Jane Jacobs in the Woo does not tweet, snapchat or instagram. Instead,Jane Jacobs in the Woo offers meandering conversation to stimulate deep thinking. How could Jane Jacobs in the Woo cut out all the interesting little tidbits. We need to know that funeral homes were often built near churches so that bodies could be easily laid to rest, that Finns brought over communal steam baths to the Laurel Clayton neighborhood where they settled. John hypothesizes that nourishing social bonds and interaction in the public sphere decreased in our neighborhoods in part because of the demise of neighborhood-based, small scale public institutions (neighborhood schools, neighborhood libraries, neighborhood associations). Healthy, livable neighborhoods have communal spaces embedded into the fabric: schools, libraries, community centers, restaurants, stores where locals can reach walking out their doors.

How the building of 290 impacted Worcester, a neighborhood by neighborhood analysis

Why a highway through Worcester

"It goes back to the federal highway program. 290 was originally called the Worcester Loop. The state conceived of it first as an idea of pulling traffic through Worcester and providing more access to Worcester from the Mass Pike. The two highways (128 and 495) were described as the inner circumferential and the outer circumferential highway. The original goal was to pull 290 all the way to 128. That part was abandoned because it would have gone through places like Sudbury and Weston where there was a lot of resistance. The route through Worcester (and this is a little bit of conjecture on my part) was to provide a way through Worcester and better traffic flow within Worcester. One of the criticisms of 290 by traffic engineers is that it has too many exits and entrances. I think that was by plan to reduce traffic congestion in the city. It is difficult when you are going to build this in a built up city."

On the road: Auburn to College Square

"The part from Auburn to College Square was never very controversial because it was partly open space or adjacent to railroad tracks. As it enters Worcester, it crosses Hope Avenue but that was not a residential area. On one side are industrial buildings and on the other side are cemeteries (Hope and St Johns). A little bit beyond there, it came into the college hill south Worcester neighborhood. Part of what it went through was industrial and commercial properties so there wasn’t a strong sense that residences were being destroyed. You know how it skirts the Rotmans furniture store? There were probably a couple of houses but mostly industrial property and property where things were dumped. The controversy there was taking the Holy Cross football field. The college strongly opposed that and was successful in getting the route moved."

On the road: Millbury Street neighborhood

"In the Millbury Street area, the route did go through neighborhoods. Most of that neighborhood was Irish originally, Polish and Lithuanian. There was some controversy there, east of Millbury Street paralleling Ward Street. It does create a barrier. The highway is elevated there so street that had been in existence, went under it or were dead ended. This area is still an active, ethnic neighborhood – Polish. If you went there today, you would find a lot of bars, European bakeries. It survived, maybe not the kind of way it might have."

On the road: What was once Jewish Union Hill

"The highway goes under Vernon Street at that point… the area where Water Street, Providence Street was impacted. Water Street itself got a little bit cut off from the neighborhood, largely a Jewish neighborhood at that point on lower Providence Street. S.N. Berhman talks about living on Providence Street and going down to Water Street to the Emma Goldman ice cream store and his mother telling him that was the worst thing he could ever do because she was an apostate, not a practicing Jew, irreligious if not anti-religious. That neighborhood had a lot of synagogues at that point. The big one, the one his family went to, Sharaai Torah East, is still there, condos now. Down the street was another synagogue, a wooden one called Bialystoker shul named for a town in Lithuania was taken but what was happening there had already begun, that is, a movement of a community from there to the west side. There was a big shift, a lot to do with economics, social prejudices, social standing. It’s not unusual. It’s the same thing that happened in Boston without an expressway, people moving from Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester to Newton or Brookline or wherever. The highway may have pushed this (migration) but I think it had already begun. Once WWII was over, a lot of money became available and a lot of prejudices ended or were moderated. (Vernon Hill is) still an ethnic immigrant neighborhood. It’s not Jewish anymore. Right now it’s probably Latino and African. If you went to Grafton Street today, got off 290 and went up the hill and began to walk, you’d see Liberian stores, an African church, storefront this and storefront that. What I think what happened there was 290 sped the move of some people out of the neighborhood but it also created an area where a new immigrant group would later move in. It’s where you go when you are first here and then when you are successful, you move somewhere else and the next group follows. My own guess is that there is a bit or romanticization about the neighborhood, a three decker neighborhood. The houses were fairly crowded, about 5000 square foot lots, three families probably with lots of kids. People still walked everywhere. It had that kind of vitality. It had a lot to do with compactness, compatibility, a lot of people with shared values, shared expectations. That’s common in an immigrant neighborhood. People wanted to worship together. They wanted stores that sold things that they were used to. They wanted people they could talk in their language. You find this all over the city."

On the road: Italian Shrewsbury Street

"Beyond there, you get to the Italo neighborhood. It’s almost paradoxical. You have a highway running through that changed one neighborhood quite a bit into another that didn’t change all that much. A lot of people in the Shrewsbury Street area would say that 290 created a wall between it and downtown. There’s some truth to that. It did tend to isolate the area. At the same time it has become a boom area in terms of restaurants. The route there didn’t go through the heart of the community. It went on the periphery, on Mulberry Street. It took what would have been the old Union Station tower and the area that would have been across the street from Mount Carmel, probably not residential, probably more commercial."

"Mt Carmel church symbolizes a lot of change that is taking place there. The church is old, not in good shape which I think may be true of the neighborhood. A lot of people are old and they are going to stay, see the end of their life there. Much of the rallying (to save the church) is from people who don’t live there. They see the church as a symbol but sometimes it’s a symbol that is just a symbol. It’s not a thriving, dynamic community. Religion is far less important in people’s lives. If you talk to any religious group in the city, right now with perhaps the exception of recent African immigrants, none of them are doing well."

How you decide the route of a highway through a dense city

"When you talk about routes, what is the alternative? If you go west, you go through downtown Worcester and the cost is unbelievable. If you move it east, you really move it through more residential. Then, topography plays a part. Engineers must have had a hand in this. If you go down to Shrewsbury Street, stand at east park, Cristoforo Colombo Park and you look north, what you see is about 300 feet of ledge. If you take a topographical map of Worcester and say, where can we run a highway, I suspect the route that’s followed tends to be less hilly. In the college hill neighborhood, it runs at the foot of the hill. It doesn’t go through or over Vernon Hill but through the lowest point. Frequently enough, the route of choice is the low point."

On the road: Belmont Hill and Laurel Clayton:

"Belmont Hill would have had the most mixed ethnicity of any part of the city – black, Finnish, Swedish, Irish, a mixed bag. If you come off 290 heading east, take the ramp up to Belmont Street, Liberty Street which was and is a small African-American part of the neighborhood. The Gothic church right next to 290 was a Lutheran church and then became a Catholic church and now a Chinese church. Across the street where the city housing project high rise is, that was a Swedish funeral home. That was a common practice: the funeral home was across the street from the church. If you go back to a 1900 map and can identify churches, funeral homes were frequently near one another. Literally, they didn’t have the means to move the congregation and the body. That neighborhood still has a fairly visible black presence. The Belmont Street AME Zion Church originally was on Clayton Street. Another black neighborhood was around John Street off of Lancaster Street, parallel to Highland Street. Most of the people in that neighborhood were post civil war now free who come to Worcester. Laurel Clayton had longer standing African American families, probably families of mixed Native American ancestry. "

And now it is Plumley Village… what happens when top down planners decide

"Some of Laurel Clayton was taken down for highway and some for redevelopment of Plumley Village. Plumley Village was sponsored by the State Mutual Insurance Company, named after the president of the company, H. Ladd Plumley whose wife was on the school committee in Worcester, Christine Plumley. They must have seen it as an investment. I’m not quite sure of the structure of the whole thing. Probably there was federal money available for redevelopment and housing and you needed a sponsor. The WRA has the eminent domain authority. They take, demolish and then they can resell. I would guess that State Mutual created a corporation to hold the property. Then, they sold it a long time ago. All residential.. not mixed use. The theory of the time was you build highways with grass and green space but I don’t think there is much in the way of retail or commercial. The planner decides who is going to rent the space, It’s not like the people decide, “Hey, we want a bodega”. Top down contrast to what had traditionally occurred, that groups moved into a city and somebody saw an opportunity to open a grocery store or a church or a beauty salon or whatever. You get a mixed use then and a personally invested situation rather than an insurance company or Macy’s coming in to have a branch here (obviously very top down)."

"What strikes me about Plumley Village is that it looks the same now as it did then. It replaced 4 or 5 story brick buildings with commercial space, bars. Since it had originally been a Finnish neighborhood, there were steam baths which were rare in this area. It’s a tradition being carried out by an ethnic group. There was a supermarket in that neighborhood called the coop, part of the United Cooperative Society. The Finns, in particular came from Europe with this background in going to the member owned cooperatives. They looked like real stores, probably managed professionally for the benefit of everybody. That disappeared maybe because the neighborhood was decimated. Maybe the consumer base was gone. I’m not quite sure. That neighborhood did get impacted but like Providence Street, there were already changes taking place. The Lutheran Church merged with two others to build the church across the street from the art museum. So, there was a move out of the neighborhood, the process of success and affluence. Living in a three decker was fine but living in a three bedroom house on Beechmont Street was finer. That’s the model and the expectation. A lot of immigrants came thinking if they work hard, they would succeed and move up. They would go from moving in a tenement to a small house to a bigger house."

Where is Worcester now bustling

"If you go through Worcester right now and you look for a lot of activity on the street, you find a fair amount of it on Water Street, a spillover from what is happening on Green Street. Housing is beginning to come back there. People can walk from those upscale condos to Water Street. All of that means a fair amount of activity. Shrewsbury Street, you see it at night with restaurant activity but you don’t see lots of little stores where they are going in but there is some. I got involved with some people in Quinsigamond Village and they were trying to get more people on the street. This friend of mine bought a church that was abandoned and he moved it to a different location in Quinsigamond Village. It was a small church. He leased part of it as a café and his wife ran a children’s bookstore downstairs in the basement. It was a great idea because you had people going to the café and then downstairs. There was a florist down the street and a baker but none of this has reached critical mass."

Missing Main Street

"After WWII, the stores were open late on Wednesday nights. You look at pictures of the sidewalks. They’re jammed with people! People would take the bus. They were not driving and that is a part of it. The range of where you can go is much farther now. As I understand it, retail has shifted from malls to online. Malls are in trouble. You wonder about small retailers anyway. There was a story in the Telegram the other day about this small gift shop, Putnam in Webster Square plaza. The family that started it fifty years ago said nowadays they can’t make it any longer. The store needs a little sprucing up but they can’t get any loans. When they show their financials, there’s just not enough coming in. Look at bookstores (and I’m guilty of this), people buy books on Amazon. A friend of mine used to run a bookstore in Webster Square, classic used books, creaky shelves, dusty, he went out of business as a store. He still does sell but it is all online. Half the joy of going there was just to rummage. For bookstores in Cambridge, part of the problem is the rents. Landlords can charge phenomenal rents and the only ones who can pay them are the chains."

Jane Jacobs’ kind of skepticism of urban planners and developers

"Planners of Lincoln center said, “Here we will put everything all together. Here we will have the opera. Here we will have the symphony.” It didn’t develop naturally. People in Worcester talk about an arts district. That’s fine if you define a district that is already there. So, you have an art museum, a small hall next door where you have concerts. That’s fine but if you say, “Oh, we’re going to have an arts district and we’re going to build this”, it’s a little bit different."

"Developers, I would see them coming to meetings, they would come in with all these beautiful drawings. Then, you have to keep looking at the bottom because it says, “architects rending of WHAT MIGHT BE!” The architect shows you this wonderful building with lots of people standing around it, beautiful treesWouldn’t you rather have that than this two story buildings with little stores with scruffy looking people?"

What Jane Jacobs would say if she came to Worcester

"If she were to come here, I think she would say, “Get people to live downtown.” Once you get an X amount of people, there will be a market (she wouldn’t like that term!) for certain kinds of stores and restaurants. The more of that, the more other people will want to live downtown. Then, it becomes a success."

The importance of density

"In Worcester, a lot of building lots were 5000 square feet. In this neighborhood, it is 10000, but you go to suburbs and it is 30000, 40000. You don’t even see your neighbors! Maybe that’s what a lot of people wanted. It’s, “Oh, they live down there. I didn’t know!” I think sometimes people moved to the suburbs because of schools, sometimes for legitimate reasons and sometimes based on prejudices. Their kids now are long gone so they’re sitting in splendid isolation on their 30,000 square feet that needs to be mowed. Maybe they are saying, “Maybe I’ll move back where I can get to places without having to drive.” People live much longer now. "

In the spirit of our conversation about the impact of 290, John pointed out that Thomas O'Flynn, the author of this 1910 volume was the principal of the Ledge Street School that was demolished to make room for the highway.

Growing up in Greendale – neighborhoods thrived because we had neighborhood schools, neighborhood libraries, neighborhood associations

"We were the next to last house on our street. After that was just woods. I had an uncle that lived not too far away. He had a small apple orchard. We lived in a city but it wasn’t very “citified”. But the other way towards West Boylston Street, there would be stores, a spa that sold lunch and sundries. Next door was a baker, then a clothing store, then a cleaner, then a grocery store and the school was on the next street. Maybe the loss of neighborhood schools is what is going on too. (He then discusses the loss of neighborhood libraries due to budget cuts and the importance of neighborhood associations) What you want is those to revive."

Why we have less social capital now

"When we go out to dinner, Joyce, what I increasingly notice is that a couple will come in or two couples and what people aren’t doing is talking to one another. Everybody’s got their phone out. I’m just astounded sometimes. You see people sitting across from one another and they are both glued on this. (John points to his hand and pretends he is using a cell phone) The sense of community is not as strong as it once was. It shows up in elections too. One of the reasons why turn-out is declining is because there is less sense of community. Some of it is rootedness, People move all over the place for work. People don’t stay put. They tend to get a job offer in California and then move from there to Omaha then you go to Phoenix."

Fun to be mayor

"It was fun to be mayor because you went to everything. You get invited to everything. Groups I had no great familiarity with would invite me to come and speak or be a part of a program. What it meant for me was that I got to meet all kinds of interesting people. I worked at it too. If I got invited to an event of a particular ethnic group, I did my best to find out a lot about them before I went and that meant I appreciated more what they were doing. There was a kind of reciprocity too because I went as mayor meant something to them."

One of the accomplishments he is most proud of during his city council years

"There was surge of development in the late 80s. Builders were optioning vast tracts of land and were going to build condos. Worcester had a lot of open space. The real estate market was very high. People were bidding up prices. The city’s zoning and building ordinances couldn’t keep up with what was going on. So, I proposed a moratorium on new permits for a year or so to give the city time to re-examine, revise the zoning ordinance. I was afraid what was going to happen was you get all this cheap building thrown up all over the city which would destroy the landscape. There were hilltops they were digging into. A rainstorm would come along and it would just wash out. It was just awful. I proposed that and I did get the city council to agree. The Telegram and Gazette went crazy… I was standing in the way of progress. I was a neanderthal. I forget what else. Yet, I think in the long run, it was certainly the right thing to do. Worcester had this ambience, this kind of mixture of urban and open space, lots of urban activity but at the same time you didn’t have to drive 50 miles to get to open space."